Trump’s efforts to block publication of books highlights concerns about prior restraint orders

So far this summer, President Trump and members of his family have made several attempts to prevent the publication of high-profile books offering an inside look at the president and his administration.

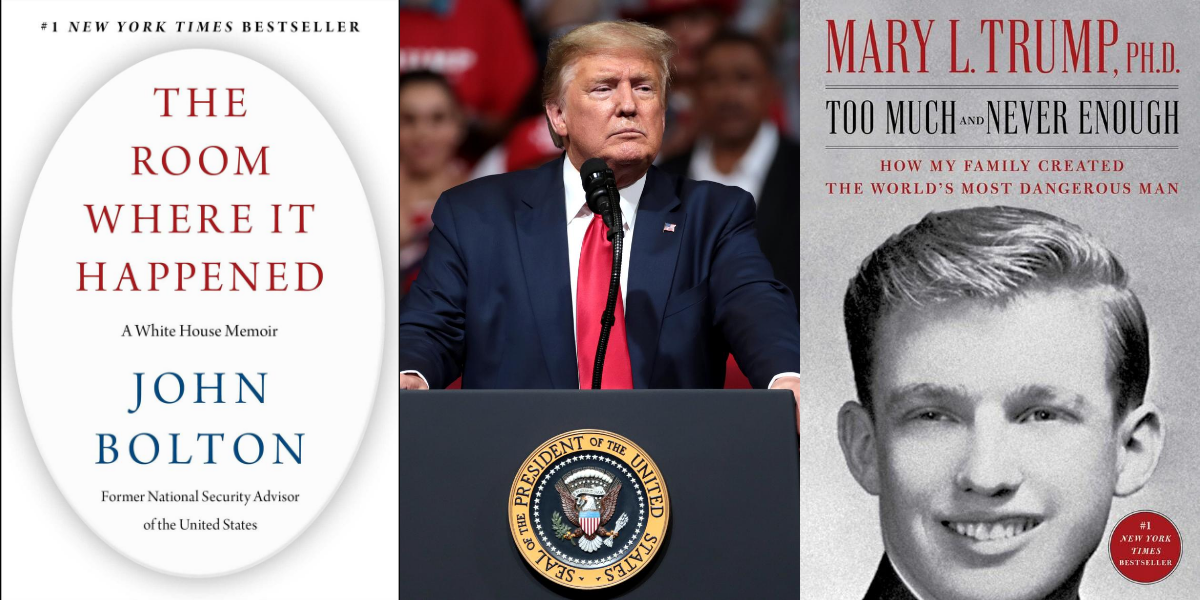

In June, the Trump administration tried to stop John Bolton from publishing a memoir about his time as the president’s former national security adviser. Two weeks later, the president’s brother sued his niece, Mary Trump, and her publisher over her book, “Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man.” And most recently, a federal judge found that the government returned the president’s former lawyer, Michael Cohen, to prison in retaliation for his plan to publish a book about President Trump.

These efforts to block books about the president are all examples of unconstitutional prior restraints, government orders meant to prohibit journalists, news organizations and others from publishing information. Prior restraints are considered particularly egregious violations of the First Amendment because they prevent information from being published in the first instance.

While prior restraints have garnered significant public attention this summer, attempts by government officials to prevent publication are nothing new — and neither are the Reporters Committee’s efforts to fight them.

The U.S. Supreme Court has established key legal precedents rejecting prior restraint orders, and Reporters Committee attorneys frequently cite these landmark cases to defend authors, journalists and news organizations against efforts to prevent publication — as they did in friend-of-the-court briefs they filed in the Mary Trump and John Bolton lawsuits.

But the Reporters Committee has also challenged prior restraints in a wide variety of other cases in federal and state courts around the country, cases that have received much less coverage but that similarly threaten First Amendment freedoms.

‘This is of the essence of censorship’

In 1931, The U.S. Supreme Court established the prior restraint doctrine in Near v. Minnesota. In the case, an anti-Semitic Minnesota newspaper, The Saturday Press, accused local officials of being involved with gangsters. In response, the officials sought a permanent injunction against the newspaper through an obscure Minnesota censorship statute. The Supreme Court found the statute vague and concluded that it was a prior restraint. In the opinion, the court cited Sir William Blackstone, whose 18th century “Commentaries on the Laws of England” greatly influenced the First Amendment:

“The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state; but this consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matters when published. Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public; to forbid this is to destroy the freedom of the press; but if he publishes what is improper, mischievous or illegal, he must take the consequence of his own temerity.”

Near set a precedent for later prior restraint cases, most notably the Supreme Court’s decision in New York Times Company v. United States. In 1971, the Supreme Court rejected a Nixon administration lawsuit seeking to prevent The New York Times and The Washington Post from publishing the “Pentagon Papers,” a massive trove of documents detailing U.S. military involvement in Vietnam. Nixon argued that publishing the information could damage national security interests, but in a 6-3 decision, the Court found that the First Amendment prohibited the government from prohibiting its publication.

In his opinion, Justice Hugo L. Black said, “Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government.”

The Pentagon Papers case set the standard that there is a “heavy presumption against [the] constitutional validity” of prior restraint, which can only be overcome in the most extraordinary circumstances. It also solidified the news media’s role as an external check on the government’s actions — an integral part of a well-oiled democracy.

Four years later, the Court upheld the Pentagon Papers case in Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart, finding that prior restraint still remains unconstitutional, absent the most extraordinary circumstances. In Nebraska, a state trial judge issued a “gag order” preventing members of the press and public from reporting suspects’ confessions related to a murder trial in 1975, concerned that widespread media coverage might bias a jury. When the Supreme Court heard the case a year later, its unanimous decision held that the “heavy burden imposed as a condition to securing a prior restraint was not met in this case.”

Citing Near and New York Times, Justice Warren Burger wrote in the Court’s opinion, “The thread running through all these cases is that prior restraints on speech and publication are the most serious and the least tolerable infringement on First Amendment rights.”

A threat against ‘the liberty of the American people’

As an organization committed to maintaining First Amendment freedoms, the Reporters Committee has long fought prior restraints in federal and state courts. In addition to filing briefs in support of Mary Trump and John Bolton, Reporters Committee attorneys have argued against unconstitutional government orders to silence journalists, news organizations, think tanks, and even tech companies.

In 2018, for example, the Reporters Committee led dozens of media organizations in urging the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit to block a prior restraint on the Los Angeles Times. The Reporters Committee’s friend-of-the-court letter came in response to a temporary restraining order directing the newspaper to delete an article about a plea deal agreed to by a narcotics detective accused of working with the Mexican Mafia.

The plea agreement was supposed to be filed under seal but was mistakenly made publicly available in PACER, an online database for court documents. The judge later vacated the restraining order, allowing the Times to publish uncensored articles about the plea deal.

Also in 2018, the Reporters Committee supported the Las Vegas Journal-Review and Associated Press after a Nevada court ordered the publications to destroy and stop reporting on an autopsy report related to the Las Vegas mass shooting. In a friend-of-the-court brief filed with the Nevada Supreme Court, the Reporters Committee and the Nevada Press Association argued that the court order constituted a prior restraint and infringed upon the publications’ First Amendment rights.

“[T]he district court has ignored decades of established precedent under the First Amendment, protecting the flow of information to the public, and issued a gag order that is plainly unconstitutional,” Reporters Committee attorneys wrote in the brief. “Gag orders such as this significantly limit the ability of the press to report on topics of public concern and thus threaten the liberty of the American people.”

The Nevada Supreme Court sided with the Las Vegas Journal-Review and the Associated Press, holding that the Nevada court order amounted to an unconstitutional prior restraint.

To read about other prior restraint cases the Reporters Committee has been involved with, visit this page.

The Reporters Committee regularly files friend-of-the-court briefs and its attorneys represent journalists and news organizations pro bono in court cases that involve First Amendment freedoms, the newsgathering rights of journalists and access to public information. Stay up-to-date on our work by signing up for our monthly newsletter and following us on Twitter or Instagram.

Photo of President Trump by Gage Skidmore