A discussion with David McCraw: On being The New York Times’s top newsroom lawyer and the state of press freedom in the U.S.

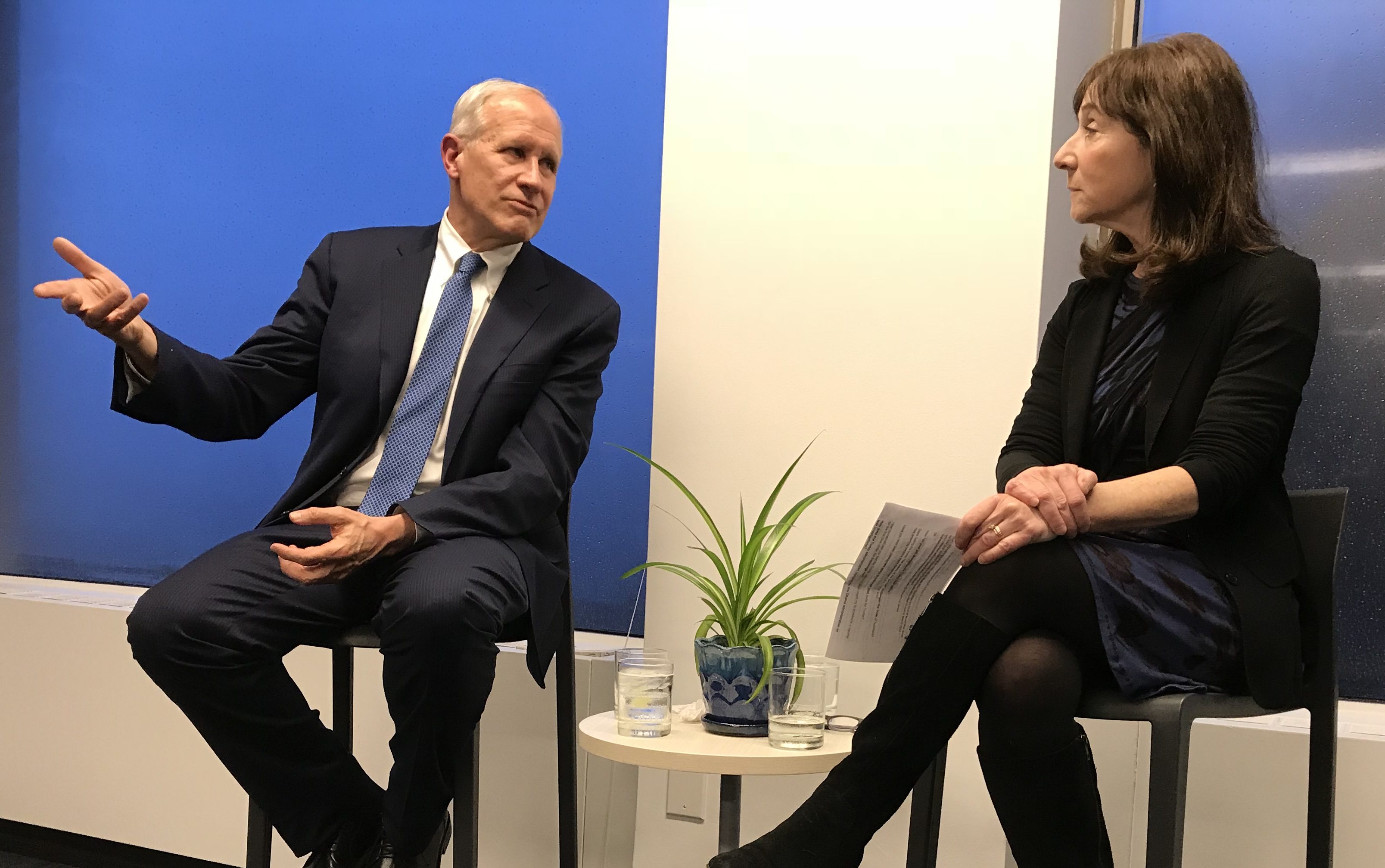

The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press hosted McCraw, in conversation with Jane Mayer, to talk about his new book, “Truth in Our Times”

After wanting to write a book for years, David McCraw, deputy general counsel for The New York Times, was given the opportunity to tell his story after his letter to President Donald Trump’s legal team went viral in 2016.

The media lawyer, and now author, explained the basis for his new book, “Truth in Our Times: Inside the Fight for Press Freedom in the Age of Alternative Facts,” in a conversation with Jane Mayer, staff writer for The New Yorker and a member of the Reporters Committee’s board, on March 21 in Washington, D.C.

Nearly 70 journalists, lawyers and First Amendment supporters gathered at the Reporters Committee headquarters to hear McCraw recount his experiences as a lawyer for The Times, many of them during tense and polarizing news moments.

Among them was The Times’s decision in September 2018 to publish an anonymous op-ed written by a senior official in the Trump administration. The piece garnered widespread attention, both for describing how the author and “many of the senior officials in [the president’s] own administration are working diligently from within to frustrate parts of his agenda and his worst inclinations,” and because it is unusual for a news outlet to run an unsigned op-ed from someone who is not a member of its editorial board.

McCraw said protecting the author’s name was a top priority — and even he doesn’t know who wrote it. Despite calls from the president urging the Department of Justice to investigate and identify the author of the piece, their name still remains secret.

“We did everything we could to protect this person’s identity,” McCraw said.

McCraw also discussed The Times’s decision to publish an article in 2017 about U.S. cyberattacks on the North Korean missile program. The story relied in part on classified information. McCraw discussed his concerns at the time about whether the Trump administration might decide to prosecute the journalists who wrote the story under the Espionage Act — something that’s never occurred before.

McCraw also noted a February 2017 conversation between then-FBI Director James Comey and the president, where the president reportedly suggested Comey consider putting reporters in prison. In the book, McCraw recounts how these details of the conversation, which occurred before The Times ran the story on North Korea, came to light through the reporting of Times journalist Michael Schmidt only after the story on North Korea had been published.

During the hour-long conversation, Mayer asked McCraw the question everyone in the room wanted to know: Has your life changed since Donald Trump was elected president?

His surprising answer? Not really.

McCraw noted that the president’s rhetoric hasn’t so much impacted the laws protecting journalism as it has the work of reporters in the field. With rhetoric from the president calling the press the “enemy of the people,” he noted an increased threat of danger to journalists.

“The Trump noise is a lot of noise,” McCraw said. “[I’m more] concerned about what it’s doing to people’s perception of the press. Even if they won’t really do anything, it’s about the effect.”

McCraw said that few know the intention of the president’s rhetoric, or what motivates his outlook on the press and The Times specifically, but that he believes Trump still cares about the opinions of the news media.

“He seems kind of obsessed with The Times,” Mayer said, as the two discussed how Trump’s early relationships with the press may have shaped his current views.

McCraw recalled the president telling The Times’s publisher, A.G. Sulzberger, in a January 2019 interview with two of The Times’s White House correspondents, “I’m sort of entitled to a great story — just one — from my newspaper.”

“There’s that feeling that he really still cares about what we think,” McCraw said.

Despite his worries, McCraw told the audience he has an optimistic outlook on the future of press freedom in both the U.S. and abroad.

Mayer asked McCraw if he still thinks there’s a possibility for a more balanced treatment of the press, and he nodded.

“It’s going to work out,” he said.

In introducing Mayer and McCraw, Reporters Committee Executive Director Bruce Brown called them “beacons” of the industry and said the work for press freedom isn’t done.

“It’s great to be with supporters, friends and funders of RCFP,” Brown said. “But we need to win more hearts and minds out there in the public.”

McCraw echoed the need for broad-based support for press freedom later in the discussion, stating that the duty to protect the press shouldn’t rest solely with journalists.

“Those of us who aren’t in the business of covering the news need to speak up,” he said. “I don’t think our reporters should be in that position.”