Journalists’ guide to HIPAA during the COVID-19 health crisis

What is HIPAA? What information about COVID-19 cases is being released?

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act is a federal law enacted in 1996 that required the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to establish federal health privacy regulations. Commonly known as the “Privacy Rule,” the regulations are intended “to assure that individuals’ health information is properly protected while allowing the flow of health information needed to provide and promote high quality health care and to protect the public’s health and well being.”

Reporters and news organizations seeking information related to the COVID-19 pandemic have frequently been told by government agencies and officials, as well as private entities in the health care system (such as nursing homes), that HIPAA prevents them from releasing certain information. But HIPAA’s applicability and scope are often misunderstood, resulting in the public being deprived of important information about the pandemic, including state and local governments’ preparedness and responses.

Reporters, government agencies, and private entities should be aware of both the limited scope of the Privacy Rule and its exceptions that may allow — or require — information related to COVID-19 to be released. For example, as discussed below, HIPAA does not bar the release of information that is required to be disclosed under state public records laws. Data about COVID-19 can also be released under a variety of exceptions.

Indeed, many jurisdictions have released detailed data about COVID-19 cases. For example:

- The South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control provides reported cases by zip code, including an estimated total number of cases by county; the state releases projections of needed hospital resources and COVID-19 deaths; state-wide data broken down by age, sex, and race/ethnicity is also available.

- The Illinois Department of Public Health releases zip code-specific data, including number of tests, positive cases, and deaths. State-wide age, race/ethnicity, and sex breakdowns for confirmed cases, completed tests, and deaths are also available.

- Maryland releases the number of confirmed cases by zip code, along with state-wide age, sex, and race/ethnicity breakdowns.

- San Francisco provides the number of confirmed cases by zip code, as well as a city-wide breakdown for gender, age groups, and race/ethnicity.

- New York City releases the number of confirmed cases by zip code, and city-wide information on age groups, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Johns Hopkins University publishes a map with updated information about which states are releasing COVID-19 data by race.

Many jurisdictions have also released information about the prevalence of COVID-19 in individual nursing homes and long-term care facilities. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, at least some facility-specific information is available in about 20 states as of April 23, 2020. The California Department of Public Health publishes a list of all skilled nursing facilities in the state by name, along with their county and counts of how many confirmed cases there are among health care workers and residents. Similarly, South Carolina officials have provided a list of the names of facilities with confirmed cases, the facility’s address, and the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in residents and/or staff.

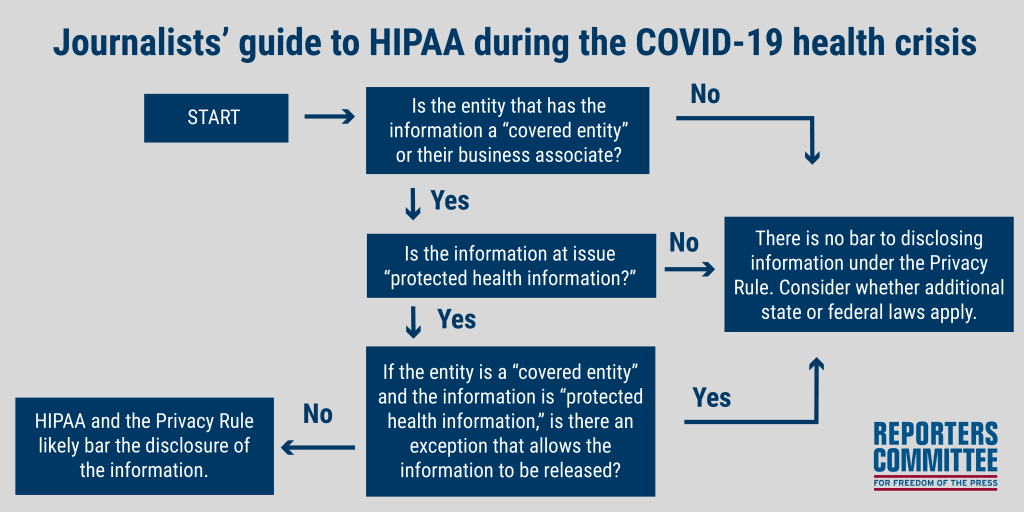

HIPAA: A basic flow chart

A basic flowchart for HIPAA and the Privacy Rule is included below and explored in more detail in the following sections.

Step 1: Who does HIPAA apply to?

HIPAA and the Privacy Rule only apply to covered entities and their business associates; they do not apply to every entity that may possess medical, health, or COVID-19 information. If the entity in question is not a “covered entity,” then HIPAA and the Privacy Rule do not apply.

The following three categories of entities fall within the definition of a “covered entity”:

- Health Plans, such as health, dental, vision, and prescription drug insurers, HMOs, Medicare and Medicaid supplement insurers, and employer-sponsored group health plans.

- Health Care Providers, if they electronically transmit health information in connection with certain transactions. Health care providers may include physicians, dentists, hospitals, and other entities that furnish, bill, or are paid for health care.

- Health Care Clearinghouses, such as billing services and community health management information systems.

These covered entities may also have “business associates” — persons or organizations that are not part of the covered entity’s workforce, but who work with a covered entity and are subject to the Privacy Rule. More information about covered entities and their business associates is available here.

HIPAA also recognizes “hybrid entities,” which are covered entities whose activities include both covered and non-covered functions, but who have elected to designate the components that perform covered functions as health care components. Most of the provisions of the Privacy Rule then only apply to the designated health care components of the hybrid entity. For example, state, county and local health departments may perform both covered and non-covered functions and elect to become hybrid entities.

Step 2: What kinds of information does HIPAA apply to?

Not all types of medical or health information fall within the scope of HIPAA and the Privacy Rule. The Privacy Rule applies to “protected health information,” which is generally defined as information that:

- Is created or received by a health care provider, health plan, employer, or health care clearinghouse;

- Identifies an individual (or there is a reasonable basis to believe it can be used to identify an individual); and

- That relates to:

-

- “the past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition of an individual;”

- “the provision of health care to an individual;” or

- “the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to an individual.”

-

If the information in question is not protected health information, then the Privacy Rule does not bar its disclosure.

It is important to note that protected health information may be turned into “de-identified” information that is not subject to the Privacy Rule and therefore can be released. There are two ways of de-identifying information: the “Expert Determination” method and the “Safe Harbor” method.

- Under the Expert Determination method, an expert “determines that the risk is very small that the information could be used, alone or in combination with other reasonably available information, by an anticipated recipient to identify an individual.”

- Under the Safe Harbor method, information becomes de-identified when 18 characteristics are removed, which include names, certain types of geographic information, dates, certain contact information, and biometric identifiers.

Step 3: If protected health information is requested from a covered entity, is there an exception that allows or requires the information to be released?

Even if a covered entity is asked for protected health information, HIPAA contains many exceptions that may allow or require such information to be disclosed. Several of the most relevant exceptions for reporters covering COVID-19 are identified below.

A. The “Required by Law” Exception & State Public Records Laws

Under the “required by law” exception to HIPAA, a government entity that is a “covered entity” is allowed to release “protected health information” if it is required to be released under a different law. In other words, HIPAA does not bar disclosure of records or information that are otherwise required to be released under a state’s public records law.

The “required by law” exception states that “[a] covered entity may use or disclose protected health information to the extent that such use or disclosure is required by law and the use or disclosure complies with and is limited to the relevant requirements of such law.” 45 C.F.R. § 164.512(a)(1). HHS has issued guidance that expressly recognizes that this exception allows the disclosure of information under state public records laws: “where a state public records law mandates that a covered entity disclose protected health information, the covered entity is permitted by the Privacy Rule to make the disclosure, provided the disclosure complies with and is limited to the relevant requirements of the public records law.”

The interaction between HIPAA and state public records laws is discussed in both state court decisions and guidance from state officials. For example, in 2006, the Ohio Supreme Court held that HIPAA could not bar disclosure of lead contamination-related records where disclosure was required by the Ohio Public Records Act. See State ex rel. Cincinnati Enquirer v. Daniels, 844 N.E.2d 1181 (Ohio 2006). Likewise, the Tennessee Attorney General noted in 2015 that “when Tennessee’s Public Records Act requires a covered entity to disclose [protected health information], the covered entity is permitted under HIPAA’s Privacy Rule to make the disclosure without running afoul of HIPAA as long as the disclosure complies with the Public Records Act.” Tenn. Op. Atty. Gen. No. 15-48, at *3 (Tenn. A.G. June 5, 2015).

B. The Health/Safety Exception

HIPAA also contains an exception that allows covered entities to disclose protected health information if it “is necessary to prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat to the health or safety of a person or the public” and the disclosure is to “a person or persons reasonably able to prevent or lessen the threat.” 45 C.F.R. § 164.512(j).

As illustrated by the declarations of a state of emergency, stay-at-home orders, and other measures taken across the country to combat the spread of coronavirus, COVID-19 clearly poses a serious threat to the health of the public. A strong argument can be made that providing detailed information about the prevalence of the disease in different areas and among different groups gives members of the public valuable information about the threat to them and their community, and can help inform their decisions, including to continue engaging in social distancing. Such actions by members of the public are key to “prevent[ing] or lessen[ing]” the “serious and imminent threat” posed to the public by COVID-19. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for example, has issued guidance stating, “when COVID-19 is spreading in your area, everyone should limit close contact with individuals outside your household in indoor and outdoor spaces.”

The news media is well-positioned to prevent or lessen the threat to individuals posed by COVID-19 because its primary role is to communicate information to the public. As the Supreme Court recognized decades ago, the press is “a vital source of public information. The newspapers, magazines, and other journals of the country, it is safe to say, have shed and continue to shed, more light on the public and business affairs of the nation than any other instrumentality of publicity.” Grosjean v. Am. Press Co., 297 U.S. 233, 250 (1936). And as The New York Times has reported, “[n]o single agency has provided the public with an accurate, up-to-date record of coronavirus cases, tracked to the county level.” Accordingly, entities like the New York Times, Washington Post, and Reuters have collected and disseminated comprehensive information about the prevalence of COVID-19 in the United States. State and local news media have also disseminated such information across the nation, such as the Texas Tribune, Detroit Free Press, Los Angeles Times, WRAL, The Oregonian, and others. With more data from government entities and private entities, journalists can better inform the public, who in turn can help reduce the threat of the pandemic.

C. Other Exceptions and Disclosure Authorizations

-

-

- Authorization: Protected health information can be disclosed by a covered entity if it has written, signed authorization from the individual it concerns. 45 C.F.R. § 164.508. HHS guidance itself makes clear that a covered entity may disclose a patient’s entire medical record, so long as it has the proper authorization.

- Public health authority: Protected health information can be disclosed by a covered entity to a “public health authority that is authorized by law to collect or receive such information for the purpose of preventing or controlling disease, injury, or disability.” 45 C.F.R. § 164.512(b)(i).

- Family and friends: A covered entity may disclose to a “family member, other relative, or a close personal friend of the individual, or any other person identified by the individual” protected health information that is directly relevant to their involvement with an individual’s health care. 45 C.F.R. § 164.510(b). According to HHS guidance from March 2020, that includes information that could help locate and notify family members or friends in charge of a patient’s care. Such information may be shared with “the press” and “the public at large.”

- Facility directory information: Hospitals and other health care facilities are generally allowed to provide “directory” information about an individual when they are asked about a patient by name; such information is used “to inform visitors or callers about a patient’s location in the facility and general condition.” Directory information may include:

-

- the individual’s name

- the individual’s location in the facility

- the individual’s condition described in general terms that does not communicate specific medical information about the individual (e.g., critical or stable, deceased, or treated and released), and

- the individual’s religious affiliation.

-

-