Constitutional lawyers publish children’s book on First Amendment

“If you could have any superpower, what would it be?” This question typically elicits a wide range of responses, from invisibility to flight. In their new children’s book, however, constitutional lawyers Jessica and Sandy Bohrer ask young readers to appreciate a different superpower, one that they already possess: their voice.

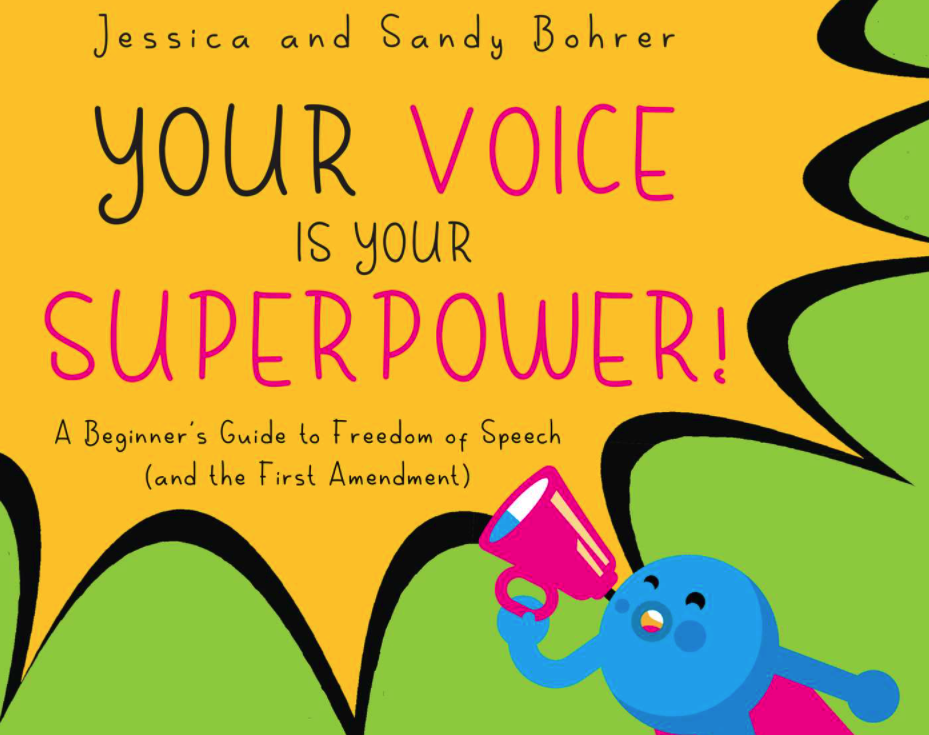

“Your Voice is Your Superpower,” published in September and intended for children ages 4-7, explains the value of our First Amendment right to free speech and encourages kids to exercise it.

The authors, a father-daughter duo, have decades of experience practicing First Amendment law. Jessica is the vice president and editorial counsel at Forbes and a member of the Leadership Council of the Committee to Protect Journalists. Her father, Sandy, is a partner at Holland & Knight who represents media organizations in lawsuits involving freedom of speech and the press. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press recently talked to Jessica and Sandy about what it was like to collaborate on the book, how they broke down the First Amendment for young readers and what they hope children will learn from the book. (This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.)

Why did you decide to write a children’s book about the First Amendment?

Jessica: We had been giving a lot of thought to the way that people, and especially young people, learn the value of freedom of speech and what the First Amendment means. We were really thinking that it’s a value, which like most values, children learn from their parents, teachers, librarians [and] other people who influence them as a young child. So we wanted to write a book that got young children down the path to believing in freedom of speech and understanding what it means, how powerful it is and how they can really use their voice.

What was it like to work on the book together?

Sandy: Jessica always wanted to write the book. It was a collaboration in a sense that she did most of the work, and I did what I could. But we’ve talked about this for a long time. Children need to be taught certain things. They aren’t born hating, but we teach them to hate. It’s pretty terrible. And, [on] a slightly lighter note, children aren’t born knowing how to listen as well as talk. We’re trying to show that you can listen as well as speak.

When did you start writing the book?

Jessica: I think we started writing the book probably three-and-a-half years ago. It’s funny because you think of a children’s book, it has very few words. It’s a picture book, and in that sense, it’s kind of like a poem. You’re trying to get your point across with very few words, but in a sense, the fewer words that you’re trying to express yourself in, the longer it takes to pick the right words. So I think it took us some time to really distill the concepts that are hard, just as my dad is saying, for some adults, including well-educated quite powerful adults, to understand how can we distill those concepts into something that even a young child could understand and really appreciate, and not only appreciate [but] feel good about what they’re learning.

It took a bunch of back and forth over those years. And then of course the illustrations and the photographs we use in the book are important as well in terms of bringing it to life. But we wanted to come up also with some concrete examples that would make it easy for the children to understand how the concepts come to life in their own experiences. So we tried to pick examples that are not just relatable for the grown-ups who are reading the book, but also where a kid could really understand like, “Oh, this is what it means to use your voice. And gosh, there’s actually a lot of different ways to use your voice.” Just as my dad was saying, sometimes one way to use your voice is actually to be quiet and not to be loud. Sometimes it’s in writing, it’s in art, it’s in joining a protest, it’s in being in a debate. There’s lots of different ways. So it took us a while to pick the ones that we felt were the most likely to resonate with the young kids, and also hopefully the parents, teachers and librarians who are reading the book to the young children, too.

As two constitutional lawyers who know the First Amendment on a high academic level, what was it like turning these difficult ideas into something that would be readable by a kindergartener or a third grader?

Sandy: It’s hard. We don’t normally talk at that language level. But it’s also true that almost no one knows what the First Amendment says. A lot of the people who know some of what it says don’t know what it means. So when you see someone say, “I have a First Amendment right to not wear a mask,” that’s not a First Amendment right, that has nothing to do with the First Amendment. But you’re trying to introduce children to the concept, and if you think about all of our First Amendment rights, they’re all kind of built on speech. So religion is built on speech. Freedom of the press is built on speech. Petitioning the government is built on speech, and children can understand that. … You almost have to be a child psychologist to figure out what words work, but we tried to use small enough words so a kid wouldn’t trip over it just so we [can] show off how smart we are.

The book frames having and using one’s voice as a superpower. Why did you choose to use superheroes to explain the First Amendment?

Jessica: Well, I think superheroes are something that certainly all young children are familiar with and get excited about. But the most important use for us of that framing was to let children understand that having a voice is something that everyone has and that makes them powerful. That means we’re all powerful. We all have a unique voice to use. So taking the idea that: What do you think about when you think of a superhero? Is it somebody who’s rescuing someone who is stuck in a building or a tree? Or, could it be something as simple as the way that you use your voice? And I think hopefully that will resonate with kids who will walk away feeling like, “Wow, I actually have a superpower that’s right within me, and that makes me special. That makes me powerful.”

What are you hoping children will learn from reading your book?

Jessica: The hope is that they’ll come out understanding what it is to use your voice and how powerful and how great it can be to use their voices. I hope that they will start to use that right and feel that power in real life. I think a lot of the subjects that we talk about in the book are things that children are seeing unfold in front of their eyes. Many children have been to protests, or they’ve had a protest down their block. They’ve been watching the news and seeing there’s people debating, they’re understanding that there’s an election coming up and people are having a lot of conversations about who’s running for office. And there’s the COVID pandemic, and they’re understanding all of these things are very difficult to understand, and it can be kind of overwhelming. So hopefully this helps them understand where they can play a part in their community, in their family and their environment. I think hopefully they’ll walk out of reading the book, and use their voice, whether it’s to write a letter, to write a sign, to tell someone what they’re thinking or feeling, [or] to be a better listener when someone else is telling them what they’re thinking or feeling. I hope that they’ll feel like they’re little superheroes out there using their voices.

The Reporters Committee regularly files friend-of-the-court briefs and its attorneys represent journalists and news organizations pro bono in court cases that involve First Amendment freedoms, the newsgathering rights of journalists and access to public information. Stay up-to-date on our work by signing up for our monthly newsletter and following us on Twitter or Instagram.