New Jersey Supreme Court affirms public right to access records on law enforcement misconduct

In back-to-back victories for government transparency and accountability, the New Jersey Supreme Court issued unanimous decisions in March ordering the disclosure of records concerning law enforcement misconduct.

In both cases, the state Supreme Court referenced arguments the Reporters Committee made in friend-of-the-court briefs urging the court to make the records public.

The two cases concerned particularly egregious reports of misconduct by law enforcement officers in New Jersey. In the case decided first, Libertarians for Transparent Government v. Cumberland County, the state Supreme Court ordered the release of a settlement agreement reached between Cumberland County and a corrections officer who had been accused of sexually abusing a female detainee, holding that the record was subject to disclosure under the state’s Open Public Records Act. In the second case, Rivera v. Union County Prosecutor’s Office, the court concluded that information from an internal affairs investigation into a police department director’s use of racist and sexist slurs must be released under the common law.

Though the court ruled in favor of disclosing records on different legal bases, both rulings are an important step toward increased transparency in government, especially law enforcement.

“They reaffirm the importance of access to records that shine a light on law enforcement operations and misconduct at this really unique moment in time,” said Reporters Committee Staff Attorney Gunita Singh.

The rulings also set important precedent for other courts in deciding open records cases.

“In dynamic areas of the law like this, courts look at what neighboring jurisdictions are doing,” Singh said. “The fact that the New Jersey Supreme Court has had two decisions one week apart that reaffirm the importance of using public records to foster accountability of law enforcement is really inspiring because other states are absolutely going to look at these cases.”

Libertarians for Transparent Government v. Cumberland County

When Libertarians for Transparent Government learned that a corrections officer had admitted to sexually abusing an inmate at the Cumberland County Jail, the nonprofit group filed an OPRA request with the county seeking the settlement agreement the county had reached with the officer. County officials claimed the settlement was exempt from disclosure under the state’s public records law because it was a personnel record. Instead of releasing the agreement, the county provided some information in a written statement and claimed that the officer was terminated.

As it turned out, however, the county’s statement was false: The corrections officer was allowed to retire in good standing and take a reduced pension.

Libertarians for Transparent Government sued the county, arguing that it had the right to access the agreement under OPRA and the common law. A trial court held that the settlement should be released with certain personnel information redacted. However, an appeals court reversed, holding that the entire settlement was exempt from disclosure under OPRA.

After Libertarians for Transparent Government asked the New Jersey Supreme Court to hear the case, the Reporters Committee and 13 news media organizations filed a friend-of-the-court brief in support of the nonprofit group’s effort to make the settlement agreement public.

In the brief, the media coalition, represented by attorney Bruce S. Rosen, argued that the appeals court had ignored a key requirement in the state’s public records law: a provision mandating the redaction of exempt information while releasing as much of the requested records as possible. The brief also stressed how access to settlement agreements makes it possible for journalists to shine a light on the conduct of public institutions and employees.

On March 7, the Supreme Court found in favor of Libertarians for Transparent Government and ordered the release of a redacted version of the settlement agreement.

Though OPRA does not mandate public access to personnel records, the Supreme Court noted, the plain text of the law includes an exception for “an individual’s name, title, position, salary, payroll record, length of service, date of separation and the reason therefor.” The records sought by the nonprofit organization clearly fell under this exception.

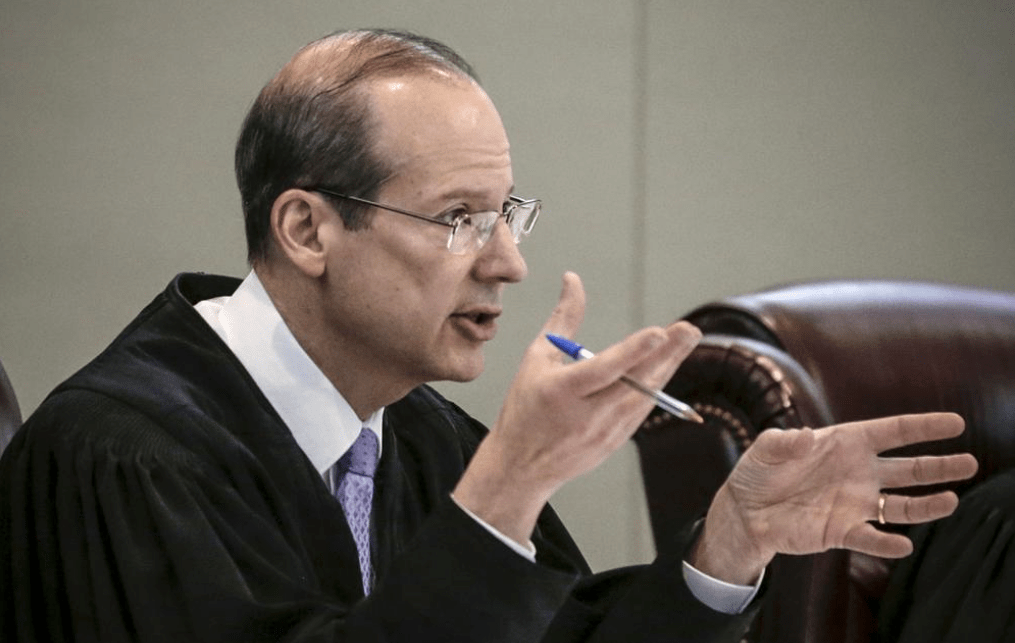

“Without access to actual documents in cases like this, the public can be left with incomplete or incorrect information,” Chief Justice Stuart Rabner wrote in the Supreme Court’s opinion, which cited both arguments made in the Reporters Committee’s brief. The chief justice also added a full-throated endorsement of open government, writing that “access to public records fosters transparency, accountability, and candor.”

Rivera v. Union County Prosecutor’s Office

In July 2019, retired police officer Richard Rivera filed an OPRA request for an internal affairs report concerning the former director of the Elizabeth, New Jersey, police department. The director had reportedly harassed members of his department using racist and sexist slurs.

When the prosecutor’s office denied his request, Rivera sued under both OPRA and the common law. Though a trial court ruled that the records should be public under OPRA, an appeals court reversed, holding that the records are available neither under OPRA nor the common law. Rivera then appealed to the Supreme Court.

Last July, the Reporters Committee, joined by a coalition of 24 news media organizations, filed a friend-of-the-court brief in support of Rivera. The media coalition, represented again by Rosen, argued that the requested records are subject to public disclosure under the common law.

The New Jersey Supreme Court agreed. While the court found that the internal affairs report was exempt from disclosure under OPRA, it should be disclosed under the common law. Under common law considerations for records requests, the court explained, the requester needs to establish the public interest in the subject matter of the record, and that interest is then balanced against the state’s interest against disclosure.

The Supreme Court remanded the case to the trial court, which had not previously conducted a balancing test under the common law. Specifically, the Supreme Court provided the following considerations as part of the balancing test: whether the alleged misconduct was substantiated; the nature of the discipline imposed; the nature of the official’s position; and the nature and seriousness of the misconduct. With these guidelines, the court found that the internal affairs report should be disclosed and left it to the trial court to determine the scope of disclosure.

“Considering the interests here, the Court notes that the public interest in disclosure is great. Racist and sexist conduct by the civilian head of a police department violates the public’s trust in law enforcement,” Chief Justice Rabner wrote in the Supreme Court’s opinion, again citing arguments made in the Reporters Committee’s amicus brief. “It undermines confidence in law enforcement officers generally, including the thousands of professionals who serve the public honorably. Public access helps deter instances of misconduct and ensure an appropriate response when misconduct occurs. Access to reports of police misconduct promotes public trust.”

Echoing the chief justice’s comments, Singh noted how the common law provides important recourse to gain access to information about how law enforcement operates.

“We’re at a pivotal moment right now where communities across the country crave greater, more meaningful access to the operations and activities of law enforcement agencies,” Singh said. “The common law right of access, like OPRA, gives folks an opportunity to get records that shed light on what law enforcement entities are doing when they are faced with complaints of misconduct by high-ranking officials — and disclosure through either forum serves the public interest.”

The Reporters Committee regularly files friend-of-the-court briefs and its attorneys represent journalists and news organizations pro bono in court cases that involve First Amendment freedoms, the newsgathering rights of journalists and access to public information. Stay up-to-date on our work by signing up for our monthly newsletter and following us on Twitter or Instagram.